- Japanetic

- Posts

- The dark side of Zen in Japan

The dark side of Zen in Japan

Why Zen isn't as peaceful as you think.

The most fanatical Japanese officers in WWII weren't Shinto priests or Confucian scholars. Zen-trained officers and clerics were.

Brian Victoria documented this in Zen at War, but Westerners still cling to their meditation apps, convinced Zen equals peace.

But Zen really is about detachment.

The samurai adopted Zen centuries earlier for practical reasons: it created warriors who wouldn't flinch. By the 1940s, Imperial Japan's military academies taught meditation alongside bayonet drills. Officers sat in silence before planning massacres.

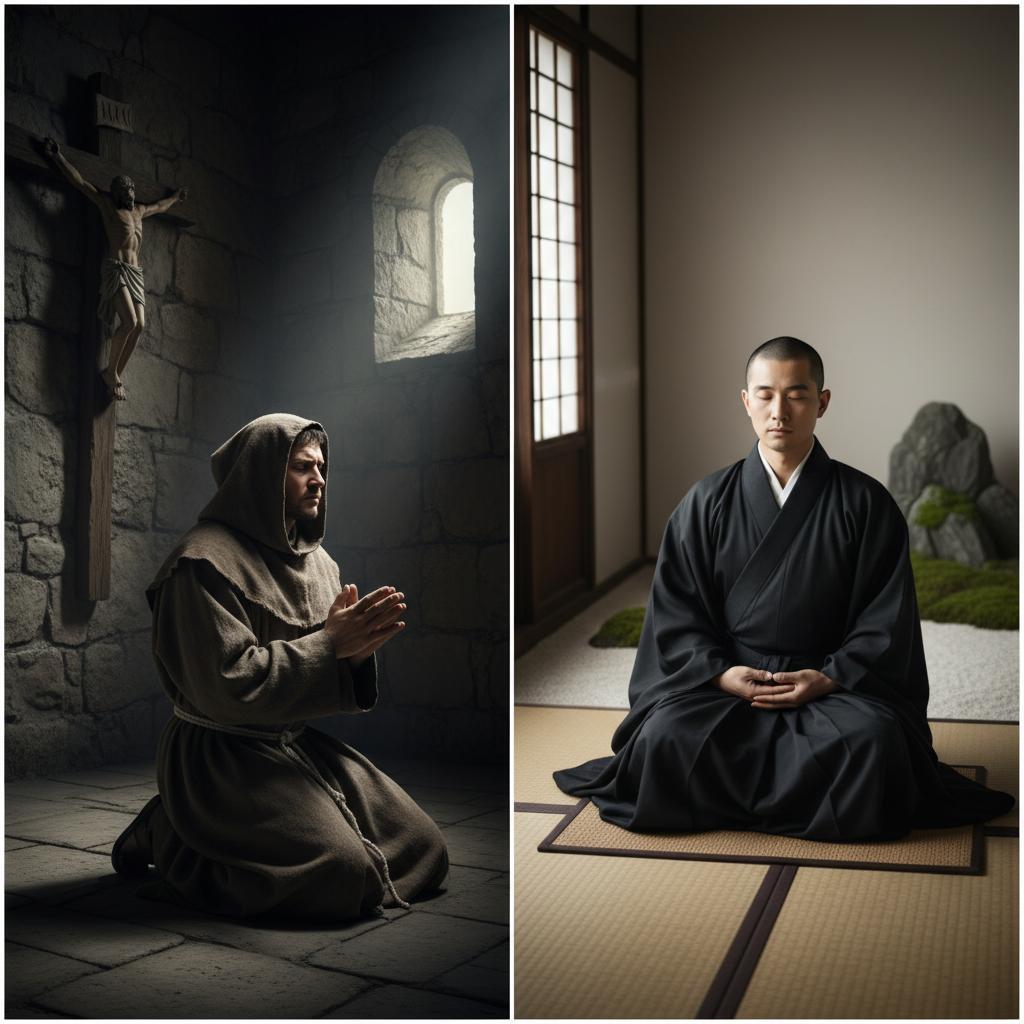

Compare that to Christian armies, which at least had to justify their violence. Crusaders needed papal declarations. Just war theory required elaborate frameworks about proportional response and protecting innocents. Zen stripped war of questions, leaving only execution.

Photo from the cover of Zen at War I upscaled and colorized with AI.

Christianity's guilt actually restrains violence

Christianity gets hate for its obsession with sin, but that framework creates something Buddhism lacks: internal brakes.

When you believe in:

Absolute moral commandments

Divine judgment

Eternal consequences

Personal responsibility before God

You hesitate. You question. You need elaborate justifications to override "Thou shalt not kill."

Christian societies developed entire institutions around managing guilt. Confession. Penance. Reformation movements when the killing got too casual.

Buddhism and Shinto? They never developed these mechanisms around guilt because they never needed them.

The moral vacuum in Japan

Shinto — Japan’s indigenous religion — has no moral code. Just purity rituals and nature spirits.

What counts as wrong? Whatever disrupts harmony. What disrupts harmony? Whatever the village says. It's pure social consensus with no higher authority to appeal to.

No commandments. No sin. No judgment day.

Sex before marriage? Fine if nobody's bothered. Killing enemies? Purify yourself after. The kami don't care about your ethics. They care about your rituals.

Buddhism has precepts, not commandments. Guidelines, not laws.

The Five Precepts sound moral:

Don't kill

Don't steal

Don't lie

Don't commit sexual misconduct

Don't get intoxicated

But they're technical instructions for reducing karma, not divine laws. Break them and you accumulate suffering, not sin. No God watching. No hell waiting. Just cause and effect, like touching a hot stove.

More importantly, these rules are negotiable. Mahayana Buddhism developed the concept of "skillful means", where you could break precepts if it helped others reach enlightenment. Japanese Zen took this further.

Amaterasu, Goddess of the sun and universe in Shintoism

Japan's selective Confucian adoption

Confucianism actually has moral content. Real rules about behavior, hierarchy, relationships.

China internalized these completely. Korea went even harder, turning Neo-Confucianism into state religion. Both societies developed extreme sexual morality:

Widow suicide as virtue

Foot-binding as purity symbol

Female seclusion from unrelated men

Japan? They took what they needed and ignored the rest.

They adopted:

Hierarchy when it supported the samurai class

Filial piety when it kept families stable

Education systems when they needed bureaucrats

They rejected:

Sexual puritanism (kept their pleasure quarters)

Widow chastity (remarriage stayed acceptable)

Gender segregation (women worked in mixed spaces)

Why? Because Japan never let Confucianism override native traditions. They used it like a tool, not a foundation. When Shinto's permissiveness conflicted with Confucian strictness, Shinto won.

Confucius shrine in Nagasaki

The result: collective discipline with almost no room for individual restraint

Without Christianity's guilt mechanism or even Confucianism's full moral framework, Japan developed something unique: social consensus as the only morality.

The group decides what's right. The group decides who dies. The group decides when to fight.

No individual can appeal to higher law. No personal relationship with divinity creates competing loyalty. Even Buddhism's "compassion" became subordinate to group harmony.

This made Japanese society incredibly disciplined but also incredibly dangerous. When the collective decided on war, there were no internal objections. No tradition of conscientious objection. No competing moral framework to create resistance.

Buddhist monks didn't protest the war. They provided the mental technology to fight it better.

Why this matters now

Modern Westerners are importing Buddhism's detachment without understanding what they're giving up.

Meditation apps hit a billion downloads. Churches empty out. Everyone wants the calm without the guilt, the mindfulness without the judgment. Silicon Valley CEOs do vipassana retreats between union-busting meetings. Wall Street traders meditate before destroying pension funds.

They're building the same moral vacuum Japan perfected.

Christianity's moral absolutism creates hypocrites, but it also creates resisters. Its obsession with sin generates guilt, but guilt generates limits. Even corrupted Christianity has to argue with its own texts. Has to face "love thy neighbor" before launching wars.

Remove that framework and what's left? Breathwork and efficiency. Detachment and optimization. The same tools that helped samurai kill without flinching now help executives fire thousands without losing sleep.

But at least they'll be mindful about it…