- Japanetic

- Posts

- History of rules in Japan: From samurai honor to salaryman order

History of rules in Japan: From samurai honor to salaryman order

Learn how chaos and rice are the foundations for these rules.

This newsletter explores the history of rules in Japan and is tied to a new section on the main Japanetic website with 53 of these rules organized neatly to quickly grasp them.

Walk through Japan for just a few days. You'll see it everywhere: the rule obsession.

Signs telling you exactly how to line up on the train platform. Neighborhood associations dictating trash sorting down to microscopic detail. Workplaces where employees clock in early, clock out late, and still apologize for not doing enough.

But where does this come from? Why did Japanese culture tie its identity so closely to strict order, harmony, and collective conformity?

History did this. The chaos of the Warring States, the ethos of the samurai, and the unique way Japanese society transformed the meaning of “honor.”

TL;DR

Japan's strict rule-following culture stems from:

Historical trauma: 300 years of civil war created deep fear of chaos

Samurai transformation: Warriors became bureaucrats, making rule-following a matter of honor

Collective shame culture: Breaking rules means disgracing your entire group

Agricultural necessity: Rice farming required absolute cooperation for survival

Systematic reinforcement: The Tokugawa regime codified these values into everyday life

Chaos creates order

Japan's strictness traces back to one of the most turbulent stretches in its history: the Sengoku Jidai, or Warring States period (14th–17th century).

The Mongols tried to invade Japan in the late 13th century. Typhoons saved them. The "divine winds," or kamikaze. But mobilizing thousands of samurai left a political hangover: restless warriors without proper reward or integration.

The central monarchy weakened. Local lords gained autonomy. The country descended into centuries of civil war. Every village became a fortress, every clan its own kingdom.

This chaos left a cultural scar. For nearly 300 years, ordinary Japanese lived in a world where stability could collapse at any moment. When the Tokugawa shogunate finally unified the country in the early 17th century, society reacted by building a system that prized order above everything else.

The national ethos became: better to over-regulate life than risk another collapse into civil war.

The samurai and bureaucratic honor

The Tokugawa shogunate faced a practical problem. At least 10% of the population belonged to the samurai class, yet with the wars over, there was little for these warriors to do. The solution was brilliant and long-lasting: turn the samurai into bureaucrats.

Samurai were forbidden to farm or trade. Instead, they were given posts in:

Administration and governance

Policing and security

Education and record-keeping

The same warrior ethos that once governed life-and-death combat was redirected into protocol, paperwork, and public service.

Carrying out tasks "by the book" became a matter of personal honor. A samurai official who enforced regulations to the letter was proving his virtue just as surely as if he had fought bravely on the battlefield.

This is how Japan's rules became tied to the idea of honor itself. Obsessive conformity became moral duty.

Honor, shame, and the collective

Japan's concept of honor was different from the knightly codes of Europe.

In the West, honor is often individualistic: a man's word, a family's reputation, or a duel fought over personal insult.

In Japan, honor is collective.

The samurai's loyalty was owed to his lord, not to abstract ideals. The villager's behavior reflected on the entire household and community. To step out of line was to shame your group, threatening its cohesion.

This collectivist honor created a shame-driven society:

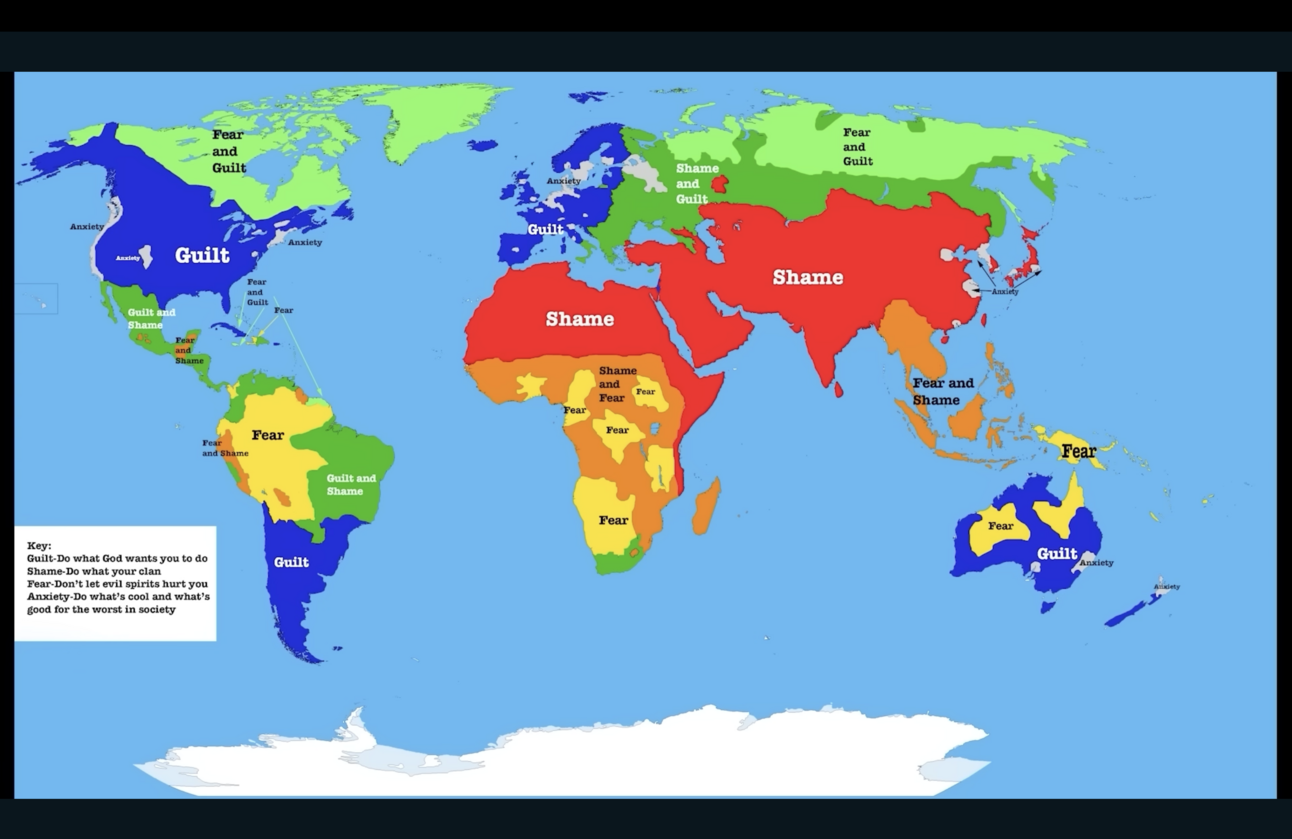

Guilt-based cultures (like much of the Christian West): wrongdoing is policed by conscience — "I did wrong, I must repent"

Shame cultures like Japan: wrongdoing is policed by community — "I broke the rules, now I have disgraced us"

Rules are not just practical guidelines. They are the invisible fabric that keeps the group intact. Obeying them is a way of preserving honor and avoiding rejection.

Rice farming and dependence

The agricultural backbone of Japan reinforced this tendency. Unlike wheat or barley, rice farming requires careful irrigation and constant cooperation. Neighbors must coordinate planting, watering, and harvesting every single day. One farmer's mistake could ruin the whole community's crop.

This kind of interdependence bred an intense sensitivity to harmony and rejection. Over centuries, it created a mindset where the group's needs always outweighed individual freedom. Rules became the social technology that ensured survival.

The Tokugawa order

From the early 1600s to the mid-1800s, the Tokugawa regime perfected a society governed by rules.

Caste restrictions: Samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants were bound to their roles with almost no mobility.

Travel controls: Villages were largely closed systems. People lived and died in the same communities for generations.

Communication protocols: Silence, indirectness, and elaborate politeness developed as ways to avoid conflict and rejection.

Religious syncretism: Shinto, Buddhism, and Confucianism all blended into a worldview that sanctified duty, hierarchy, and obedience.

Outwardly authoritarian, inwardly dynamic. Tokugawa Japan turned rules into a civilizational way of life.

Modern echoes: From salarymen to sorting trash

The legacy of this rule-bound honor system continues into modern Japan.

The salaryman system of lifetime employment, where one company takes over a man's social identity, mirrors the samurai's obligation to his lord. To quit or act independently is dishonorable.

Education and exams emphasize effort, conformity, and attention to detail.

Everyday rules like how to line up, how to bow, how to sort garbage are treated with the same seriousness that medieval villagers once treated irrigation duties. Even areas that might seem trivial to outsiders carry moral weight:

Taking off shoes at the entrance

Following rigid etiquette with business cards

Observing unwritten subway manners

These are acts of honor that signal trustworthiness and respect.

Rules, honor, and the fear of chaos

The chain is clear:

Mongol invasions created a strong samurai class leading to internal turmoil.

Warring States chaos created the demand for order.

Samurai honor was redirected into bureaucracy and protocol.

Collectivist shame tied individual behavior to group standing.

Rice farming interdependence reinforced conformity.

The Tokugawa system codified all of it into everyday life.

This is why Japan today remains one of the most rule-governed societies in the world. Not because Japanese people are "naturally" obedient, but because their entire historical experience has linked honor and survival to the strict observation of rules.

Why it matters

Understanding this connection is vital for anyone trying to make sense of Japan. What might seem like "over-regulation" or "fussiness" from a Western perspective is, in the Japanese mind, the very foundation of harmony.

To break rules in Japan is not just to cause inconvenience. It is to dishonor the group, to risk rejection, and to undermine the hard-earned stability of a society that once tore itself apart in chaos.

Japan's obsession with rules is not an accident. It is the cultural memory of centuries of war, refined into an ethic of honor, shame, and survival.

Going further

Check out the main Japanetic website to read more about the rules of Japan. Right now there are 53 rules in 10 categories, but I plan to add as many as possible to really show the madness (or genius?).

I use this recent podcast about Japan history to write this newsletter. It’s dense and almost 3-hour long but I really recommend to anyone that wants to understand Japan better.